Home

Hungary

Cardinal József Mindszenty

1956 Hungarian Revolution (My Story)

(My Eyewitness story of our Freedomfight

and Resistance against the Soviet Invasion)

50th Anniversary of our Freedomfight

My Travel and Photos Pages

Africa

America - North

America - Central

America - South

Asia

Australia

Oceania

My China pages directory

Beijing or Peking

Beijing Buses

Beijing - Forbidden City

Beijing - Prince Gong Palace

Beijing - Summer Palace

Great Wall of China

Guangzhou or Canton

Guangzhou Buses

Guangzhou trains

Hong Kong

Hong Kong Airport

Hong Kong Buses

Hong Kong - Lantau Island

Kashgar or Kashi

Kashgar Buses

Kashgar Sunday Market

Macau

Ming Dynasty Tombs

Peking Man's Caves/Zhoukoudian

Shanghai

Shanghai Buses

Shanghai Maglev / Transrapid

Shanghai Metro

Shenzhen

Shenzhen Buses

Tibet

Tibet - Lhasa

Tibet - Lhasa Monasteries

Tibet - Lhasa - Potala

Turpan or Tulufan

Turpan - Amin Mosque

Turpan - Astana Graves

Turpan - Bezeklik Caves

Turpan - Crescent Moon Lake

Turpan - Dunhuang Caves

Turpan - Echoing-Sand Mountain

Turpan - Ediqut Ruins

Turpan - Emin Minaret

Turpan - Flaming Mountains

Turpan - Gaochang Ruins

Turpan - Grape Valley

Turpan - Green Mosque

Turpan - Jesus Sutras

Turpan - Jiaohe Ruins

Turpan - Karez System

Turpan - Maza Village

Turpan - Mogao Caves

Urumchi or Urumuchi

Xian

Xian Buses

Xian - Hua Qing Pool

Xian - Silk Factory

Xian - Silk Road Monuments

Xian - Terracotta Factory

Xian - Terracotta Army Museum

Yanan

Yanan Buses

Yanan Cave Dwellings

|

China facts & history in brief

My China pages directory

My China pages directory

Map of China

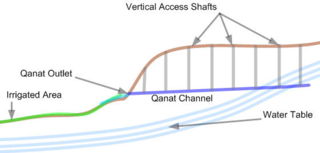

Qanat

Excerpted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A qanat (Arabic) or kareez (Persian) or karez

(Turpan) is a water management system used to provide

a reliable supply of water to human settlements or for

irrigation in hot, arid and semi-arid climates.

The widespread distribution of qanat known in different

places in their local names has confounded the question

of its origin, but the earliest evidence of this technology

dates back to ancient Persia, and spread west during the

Arab Muslim conquests, to the Iberian peninsula,

southern Italy and North Africa.

Qanats are constructed as a series of well-like

vertical shafts, connected by gently sloping tunnels.

This technique taps into subterranean water in a manner

that efficiently delivers large quantities of water

to the surface without need for pumping.

The water drains relying on gravity, with the

destination lower than the source,

which is typically an upland aquifer.

This allows water to be transported long distances

in hot dry climates without losing a large

proportion of the source water

to seepage and evaporation.

It is very common in the construction of a qanat

for the water source to be found below ground at

the foot of a range of foothills of mountains,

where the water table is closest to the surface.

From this point, the slope of the qanat is maintained

closer to level than the surface above, until the

water finally flows out of the qanat above ground.

To reach an underground aquifer qanats

must often be of extreme length.

The qanat technology was used most extensively in

areas with the an absence of larger rivers with

year-round flows sufficient to support irrigation.

Proximity of potentially fertile areas to

precipitation-rich mountains or mountain ranges.

Arid climate with its high surface evaporation

rates so that surface reservoirs and

canals would result in high losses.

An aquifer at the potentially fertile area which

is too deep for convenient use of simple wells.

The investment and organization required by the

construction and the maintenance of a qanat is

typically provided by local merchants

or landowners in small groups.

In the middle of the twentieth century, it is

estimated that approximately 50,000 qanats were

in use in Iran, each commissioned

and maintained by local users.

The qanat system has the advantage of being

relatively immune to natural disasters

(earthquakes, floods.) and human

destruction in war.

Further it is relatively insensitive to the

levels of precipitation; a qanat typically

delivers a relatively constant flow with only

gradual variations from wet to dry years.

A typical town or city in Iran and elsewhere

where the qanat is used has more than one qanat.

Fields and gardens are located both over the qanats

a short distance before they emerge from the ground

and after the surface outlet.

Water from the qanats defines both the social regions

in the city and the layout of the city.

The water is freshest, cleanest, and coolest in the

upper reaches and more prosperous people live at

the outlet or immediately upstream of the outlet.

A kariz (a small qanat) surfacing in Tehran.

When the qanat is still below grade, the

water is drawn to the surface via Ater-wells

or animal driven Persian wells.

Private subterranean reservoirs could

supply houses and buildings for domestic use

and garden irrigation as well.

Air flow from the qanat is used to cool

an underground summer room (shabestan) found

in many older houses and buildings.

Qanat or karez construction

Downstream of the outlet, the water runs through

surface canals called jubs (jubs) which run

downhill, with lateral branches to carry water to

the neighborhood, gardens and fields.

The streets normally parallel the jubs

and their lateral branches.

As a result, the cities and towns are

oriented consistent with the gradient

of the land; what is sometimes viewed

as chaotic to the western eye is a

practical response to efficient water

distribution over varying terrain.

The lower reaches of the canals are less desirable

for both residences and agriculture.

The water grows progressively more

polluted as it passes downstream.

In dry years the lower reaches are the

most likely to see substantial

reductions in flow.

Traditionally qanats are built by a group

of skilled laborers, muqannis, with hand labor.

The profession historically paid well and was

typically handed down from father to son.

The critical, initial step in qanat construction

is identification of an appropriate water source.

The search begins at the point where the alluvial fan

meets the mountains or foothills; water is more abundant

in the mountains because of orographic lifting and

excavation in the alluvial fan is relatively easy.

The muqannis follow the track of the main water courses

coming from the mountains or foothills to identify

evidence of subsurface water such as

deep-rooted vegetation or seasonal seeps.

A trial well is then dug to determine the location

of the water table and determine whether a sufficient

flow is available to justify construction.

If these prerequisites are met, then

the route is laid out aboveground.

Equipment must be assembled.

The equipment is straightforward: containers

(usually leather bags), ropes, reels to raise

the container to the surface at the shaft head,

hatchets and shovels for excavation, lights,

spirit levels or plumb bobs and string.

Depending upon the soil type, qanat liners

(usually fired clay hoops) may also be required.

Although the construction methods are simple,

the construction of a qanat requires a detailed understanding

of subterranean geology and a degree

of engineering sophistication.

The gradient of the qanat must be carefully

controlled-too shallow a gradient yields no flow -

too steep a gradient will result in excessive

erosion, collapsing the qanat.

And misreading the soil conditions leads to collapses

which at best require extensive rework and,

at worst, can be fatal for the crew.

Construction of a qanat is usually performed

by a crew of 3-4 muqannis.

For a shallow qanat, one worker typically digs the

horizontal shaft, one raises the excavated earth

from the shaft and one distributes the

excavated earth at the top.

The crew typically begins from the destination to

which the water will be delivered into the soil

and works toward the source (the test well).

Vertical shafts are excavated along the route,

separated at a distance of 20-35 m.

The separation of the shafts is a balance between

the amount of work required to excavate them and

the amount of effort required to excavate the space

between them, as well as the

ultimate maintenance effort.

In general, the shallower the qanat, the

closer the vertical shafts.

If the qanat is long, excavation may

begin from both ends at once.

Tributary channels are sometimes also

constructed to supplement the water flow.

Most qanats in Iran run less than 5 km.

The overall length of the qanat often runs up to 16 km,

while some have been measured at

~70 km in length near Kerman.

The vertical shafts usually range from 20 to 200 meters

in depth, although in Iran qanats in the province of

Khorasan have been recorded with

vertical shafts of up to 275 m.

The vertical shafts support construction and maintenance

of the underground channel as well as air interchange.

Deep shafts require intermediate platforms to

simplify the process of removing spoils.

The qanat's water-carrying channel is 50-100

cm wide and 90-150 cm high.

The channel must have a sufficient downward slope

that water flows easily.

However the downward gradient must not be so great

as to create conditions under which the water

transitions between supercritical and subcritical

flow; if this occurs, the waves which are established

result in severe erosion and can

damage or destroy the qanat.

In shorter qanats the downward gradient varies between

1:1000 and 1:1500, while in longer qanats

it may be almost horizontal.

Such precision is routinely obtained with

a spirit level and string.

In cases where the gradient is steeper, underground

waterfalls may be constructed with appropriate design

features (usually linings) to absorb the

energy with minimal erosion.

In some cases the water power has been

harnessed to drive underground mills.

If it is not possible to bring the outlet of the

qanat out near the settlement, it is necessary to

run a jub or canal overgound.

This is avoided when possible to limit pollution,

warming and water loss due to evaporation.

The construction speed depends on the depth.

At 20 meters depth, a crew of 4 people can excavate

a horizontal length of 40 meters per day.

When the vertical shaft reaches 40 meters, they can

only excavate 20 meters horizontally per day and at

60 meters in depth this drops below

5 horizontal meters per day.

Deep, long qanats (which many are) require years

and even decades to construct.

The excavated material is usually transported by

means of leather bags up the vertical shafts.

It is mounded around the vertical shaft exit,

providing a barrier that prevents windblown or

rain driven debris from entering the shafts.

From the air, these shafts look like

a string of bomb craters.

The vertical shafts may be covered to

minimize in-blown sand.

The channels of qanats must be periodically

inspected for erosion or cave-ins, cleaned

of sand and mud and otherwise repaired.

Air flow must be assured before

entry for human safety.

The value of a qanat is directly related to the

quality, volume and regularity of the water flow.

Much of the population of Iran historically depended

upon the water from qanats; the areas of population

corresponded closely to the areas

where qanats are possible.

Although a qanat was expensive to construct, its long-term

value to the community, and therefore to the group who

invested in building and maintaining it, was substantial.

Qanats were frequently split into an underground distribution

network of smaller canals called kariz

when reaching a major city.

Like Qanats, these smaller canals were below

ground to avoid contamination.

Qanats in practical application

China

Karez gallery near Turpan

Model of karez well system (Turfan Water Museum)

An oasis at Turpan in the deserts of northwestern China

uses water provided by qanat (locally called karez).

Turfan has long been the center of a fertile oasis and an

important trade center along the Silk Road's northern route,

at which time it was adjacent to the kingdoms

of Korla and Karashahr to the southwest.

The historical record of the karez system

extends back to the Han Dynasty.

The Turfan Water Museum is a Protected Area because of the

importance of the local karez

system to the history of the area.

The number of karez systems in the area is slightly

below 1,000 and the total length of the

canals is about 5,000 kilometers in length.

For a more information about

Qanat see Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This page was retrieved and condensed from

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qanat)

see Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, November 2007.

All text is available under the terms of the

GNU Free Documentation License

(see

Copyrights for details).

About Wikipedia

Disclaimers

This information was correct in November 2007. E. & O.E.

Hui Chin and I joined a conducted bus tour

from Urumchi to visit Turpan.

It was a very interesting trip and full of drama, as

there was many interesting places to visit and there

was also a number of arguments

on the bus about the tickets and

sights to be visited, the sitting arrangements on the

bus and also about the food and the quality and hygene

standard of the restaurants we have visited.

To cap it all of, my camera's battery ran flat, half

way through, our spare battery and another camera sitting

safely back at the hotel in Urumchi (laughing at our

misfortune), but a few weeks later I had even worst news,

when, after returning home, I found out that two of my

new 2Gigabyte SD memory cards, although seemed to work

perfectly at the time, have invisible pictures on them.

The pictures seem to exist alright,

with all around the 200 plus kilobyte

properties and showing as jpeg pictures, but can't be viewed.

I have lost some very interesting, unusual and irreplacable

pictures of Turpan, Urumchi, Bishkek in Kyrgizstan and pictures

of the countrysides of Kyrgizstan and Kazakstan.

____________o______O_______o____________

Now altough we were there and had our visual and phisical

experiences, I have to take advantage of using Wikipedia,

the free encyclopedia's

resources with our greatful thanks. Author.

____________o______O_______o____________

I would like to mention a few things, that was mentioned to us

during our visit to Turpan, but I do not find any mention on

the pages and articles I read before

putting this page together.

Turpan is sited in a basin (Turfan Depression),

at the second deepest hole after the Dead Sea - under

sea level.

(328ft. below sea level).

Turpan is one of the hottest place on earth, due to its

desert location and relative altitude.

Turpan also one of the driest place on earth again due

to it's location and altitude. (This last two points

make it ideal place to grow grapes and other fruit with

the Karez (water) System's help.

Some of Turpan's listed attractions may be 40+ kilometres

away, normally they still will be listed

as Turpan's attraction.

On the way to Turpan from Urumchi our bus stopped at a

fortress, as I lost the many photos I have taken of this

place - as I have explained above, now I can't find any

reference or mention of the place - can somebody help me, please?

Author.

The Karez System as operated in Turpan

|