New pages added recently:

Signs of Intelligent Life

Our Antarctica trip.

Appeal to rebuild the Regnum Marianum Church - Budapest -

Hungary - Blown up by the communists.

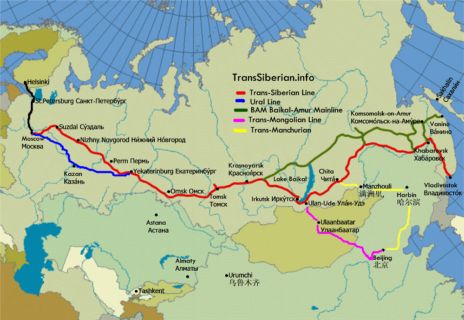

Trans-Siberian Railway

Excerpted from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

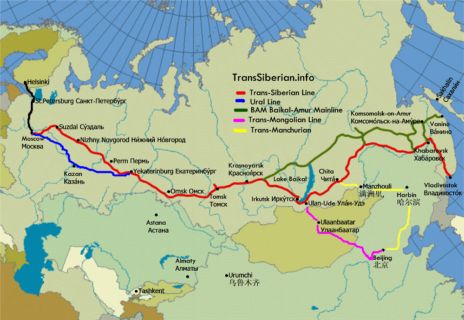

Trans-Siberian Express map courtesy Wikipedia,

the free encyclopedia.

Titan HiTours VIP Trans-Siberian Express Itinerary

DAY 1 LONDON . MOSCOW

We begin with Titan HiTours VIP Home Departure Service®

to London Heathrow airport for your direct scheduled

British Airways flight to Moscow.

On arrival we meet our tour manager and transfer to the

Sovietsky Hotel.

This evening we enjoy an included welcome dinner.

DAY 2 MOSCOW . TRANS-SIBERIAN EXPRESS

This morning we embark on a city tour of Moscow's amazing

Red Square, St Basil's Cathedral, the stunning Armoury

Chamber and the Cathedral of the Assumption.

We also visit the palatial metro system with stations draped

in chandeliers, mosaics and baroque bas-reliefs.

Following a cultural performance in a local theatre, we join

our private railway carriage and begin the spectacular

journey east.

DAY 3 TRANS-SIBERIAN EXPRESS

After leaving Moscow, the majesty of the Russian countryside

becomes apparent with the birch forests flanking the Volga,

Europe's longest river.

Savour the fine cuisine of the restaurant car and the bustling

sociability of life onboard.

DAY 4 EKATERINBURG . TRANS-SIBERIAN EXPRESS

The Ural Mountains mark the border between Europe and Asia.

Stop at Ekaterinburg, founded in 1723 by Peter the Great and

learn about its intriguing and somewhat bloody history on a city

tour, with visits including the site of the Romanov family

massacre in 1918.

Re-board the Trans-Siberian Express in the evening.

DAY 5 OMSK . TRANS-SIBERIAN EXPRESS

Following our arrival in Omsk, situated on the banks of the

Om and the north-flowing Irtysh River, we embark on a city

tour, which includes its lively Riviera, elegant architecture

and grand opera theatre, for which the city is now famous.

Later we rejoin the Trans-Siberian Express.

DAY 6 TRANS-SIBERIAN EXPRESS

The day is spent crossing Siberia, 'The Sleeping Land', and

daybreak reveals a new vista of fir forests and wild flowers,

homely cottage gardens and myriad signs of simple life in a

harsh but beautiful region.

DAY 7 IRKUTSK . TRANS-SIBERIAN EXPRESS

Our main stop today is at Irkutsk, a former Cossack military

outpost and late 19th Century gold rush town, also once known

as the 'Paris of Siberia'.

Our tour showcases tree-lined boulevards, elaborate brick

mansions and century-old wooden houses, before we rejoin the

train bound for Lake Baikal.

DAY 8 TRANS-SIBERIAN EXPRESS . LAKE BAIKAL

Lake Baikal, 'the pearl of Siberia', is the world's deepest

freshwater lake, whose crystal clear waters stretch for over

600km to the north.

To fully appreciate its magnificence, our private carriages

are attached to a steam tourist train, which follows the edge

of the lake to Port Baikal.

From there we cross to the small village of Listvyanka to

spend the night in a traditional Siberian guesthouse.

DAY 9 LAKE BAIKAL . TRANS-SIBERIAN EXPRESS

We awake to the vast natural paradise, frozen to a depth of

up to one metre during winter, while during summer, bathers

brave the still very cold waters for its promised health

benefits.

Visits include the limnological institute with a display of

the lake's unique flora and fauna, indeed we may see some

of the lake's endemic freshwater seals if we are lucky.

Evening back aboard the Trans-Siberian Express.

DAY 10 ULAN UDE . TRANS-SIBERIAN/MONGOLIA EXPRESS

Ulan Ude is unmistakably Asian and reminiscent of old

Siberia.

This unusual, laid-back city is the centre of Russia's Buddhist

community and a joy to explore on our tour.

Later, our private carriages are attached to the Trans-Mongolian

Express train, reaching Naushki, the Russian border town by

evening, continuing from the Mongolian equivalent, Sukhbaatar,

towards the world's most remote capital city,

Ulaanbaatar.

DAY 11 TRANS-MONGOLIAN EXPRESS . ULAANBAATAR

Arrive at Ulaanbaatar, a splendidly contradictory city of donkeys

and motorbikes, monumental apartment blocks and tents made of wood

and skins.

This was the homeland of the tough, well-drilled horsemen, who for

over 500 years from the 13th Century plundered and occupied lands

and cities from the Yellow River to the Danube.

At daybreak classic scenes of a traditional nomadic lifestyle greet

us as the train winds across the Mongolian Steppe and into the

capital.

We bid farewell to our private carriages and are transferred to

Sunjin Grand Hotel for an overnight stay.

DAY 12 TERELJ NATIONAL PARK

We transfer to Terelj National Park; our accommodation for

the night is the traditional round tents (Gers) of the Mongolian

nomads, set amongst the beautiful alpine scenery of the national

park.

Our Ger-stay is one of the great highlights of the journey and

we have the opportunity to sample some of the traditional food

and drink of Mongolia.

Enjoy a walk through the countryside to Turtle Rock, relax at

camp and enjoy a display of the traditional Mongolian skills

of archery, horsemanship & wrestling.

DAY 13 ULAANBAATAR . BEIJING

After sightseeing stops back in the capital at the Gandan Hiid

Monastery, providing an enlightening insight into the religious

beliefs of the Mongolians, and the superb National History

Museum of Mongolia, we transfer to the airport for our Air

China flight to Beijing.

On arrival we transfer to the Jianguo Hotel for a two night

stay.

This evening a sumptuous Peking duck banquet provides the

opportunity to reflect on all that we have seen and

experienced together.

DAY 14 BEIJING

Our full day guided tour includes Beijing's most famous

areas.

We visit the fabulous Great Wall of China, on which sections

reach up to 15 metres in height.

Later we visit Tiananmen Square and the serene Forbidden City,

a complex of imperial palaces that were home to the Ming and

Qing emperors for over 500 years.

DAY 15 BEIJING . LONDON

This morning we transfer to the airport for our return British

Airways direct flight to London Heathrow.

On arrival our staff will greet you and transfer you to Titan

HiTours transport for your journey home to your own

front door.

Further information about this tour can be found

here.

Some of my photos of the Trans-Siberian Express.

You can click on these photos for an enlargement

Trans-Siberian Railway

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Trans-Siberian Express map courtesy Wikipedia,

the free encyclopedia.

The Trans-Siberian Railway or Trans-Siberian Railroad

(Транссибирская магистраль, Транссиб in

Russian, or Transsibirskaya magistral', Transsib) is a network of railways

connecting Moscow and European Russia with the Russian Far East

provinces, Mongolia, China and the Sea of Japan.

Today, the railway is part of the Eurasian Land Bridge.

History

The plans and funding for construction of the Trans-Siberian

Railway to connect the capital, St. Petersburg, with the

Pacific Ocean port of Vladivostok were approved by Tsar

Alexander II in St. Petersburg.

His son, Tsar Alexander III supervised the construction;

the Tsar appointed Sergei Witte Director of Railway Affairs

in 1889.

The Imperial State Budget spent 1.455 billion rubles from

1891 to 1913 on the railway's construction, an expenditure

record which was surpassed only by the military budget in

World War I.

In March 1891, the future Tsar Nicholas II personally opened

and blessed the construction of the Far East segment of the

Trans-Siberian Railway during his stop at Vladivostok, after

visiting Japan at the end of his journey around the world.

Nicholas II made notes in his diary about his anticipation of

travelling in the comfort of The Tsar's Train across the

unspoiled wilderness of Siberia.

The Tsar's Train was designed and built in St. Petersburg

to serve as the main mobile office of the Tsar and his staff

for travelling across Russia.

The main route of the Trans-Siberian originates in St.

Petersburg at Moskovsky Vokzal, runs through Moscow,

Chelyabinsk, Omsk, Novosibirsk, Irkutsk, Ulan-Ude, Chita,

Blagoveshchensk and Khabarovsk to Vladivostok via southern

Siberia and was built from 1891 to 1916 under the supervision

of government ministers of Russia who were personally appointed

by the Tsar Alexander III and by his son, Tsar Nicholas II.

The additional Chinese Eastern Railway was constructed as the

Russo-Chinese part of the Trans-Siberian Railway, connecting

Russia with China and providing a shorter route to Vladivostok

and it was operated by a Russian staff and administration based

in Harbin.

The Trans-Siberian Railway is often associated with the main

transcontinental Russian train that connects hundreds of large

and small cities of the European and Asian parts of Russia.

At 9,259 kilometres (5,753 miles), spanning a record 7 time zones

and taking several days to complete the journey, it is the

third-longest single continuous service in the world, after the

Moscow-Pyongyang (10,267 km, 6,380 mi) and the Kiev-Vladivostok

(11,085 km, 6,888 mi) services, both of which also follow the

Trans-Siberian for much of their routes.

The route was opened by Tsarevich Nicholas Alexandrovitch of

Russia after his eastern journey ended.

A second primary route is the Trans-Manchurian, which coincides

with the Trans-Siberian as far as Tarskaya (a stop 12 km east of

Karymskaya, in Zabaykalsky Krai), about 1,000 km east of Lake

Baikal.

From Tarskaya the Trans-Manchurian heads southeast, via Harbin

and Mudanjiang in China's Northeastern Provinces (from where a

connection to Beijing is used by one of Moscow-Beijing trains),

joining with the main route in Ussuriysk just north of

Vladivostok.

This is the shortest and the oldest railway route to

Vladivostok.

Some trains split at Shenyang, China, with a portion of the

service continuing to Pyongyang, North Korea.

The third primary route is the Trans-Mongolian Railway, which

coincides with the Trans-Siberian as far as Ulan Ude on Lake

Baikal's eastern shore.

From Ulan-Ude the Trans-Mongolian heads south to Ulaan-Baatar

before making its way southeast to Beijing.

In 1991, a fourth route running further to the north was finally

completed, after more than five decades of sporadic work.

Known as the Baikal Amur Mainline (BAM), this recent extension

departs from the Trans-Siberian line at Taishet several hundred

miles west of Lake Baikal and passes the lake at its northernmost

extremity.

It crosses the Amur River at Komsomolsk-na-Amure (north of

Khabarovsk), and reaches the Pacific at Sovetskaya Gavan.

War and revolution

After the revolution of 1917, the railway served as the vital line

of communication for the Czechoslovak Legion and the Allied armies

that landed troops at Vladivostok during the Siberian Intervention

of the Russian Civil War.

These forces supported the White Russian government of Admiral

Aleksandr Kolchak, based in Omsk, and White Russian soldiers

fighting the Bolsheviks on the

Ural Front.

The intervention was weakened, and ultimately defeated, by partisan

fighters who

blew up bridges and sections of track, particularly in

the volatile region between

Krasnoyarsk and Chita.

The Trans-Siberian also played a very direct role during parts of

Russia's history, with the Czechoslovak Legion using heavily armed

and armoured trains to control large amounts of the railway (and of

Russia itself) during the Russian Civil War at the end of

World War I.

As one of the few organised fighting forces left in the aftermath of

the Imperial collapse, and before the Red Army took control, the Czechs

and Slovaks were able to take use their organisation and the resources

of the railway to establish a temporary zone of control before eventually

continuing onwards towards Vladivostok, from where they emigrated back to

Czechoslovakia through Vancouver in Canada, through Canada to Europe, or

the Panama Canal to Europe also through Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Port

Said and Terst.

Demand and design

In the late 19th century, the development of Siberia was hampered by

poor transport links within the region as well as between Siberia and

the rest of the country.

Aside from the Great Siberian Route, good roads suitable for wheeled

transport were few and far between.

For about five months of the year, rivers were the main means of

transportation; during the cold half of the year, cargo and passengers

traveled by horse-drawn sleds over the winter roads, many of which

were the same rivers, now ice-covered.

The first steamboat on the River Ob, Nikita Myasnikov's Osnova, was

launched in 1844; but the early starts were difficult, and it was

not until 1857 that steamboat shipping started developing on the Ob

system in a serious way. Steamboats started operating on the Yenisei

in 1863, on the Lena and Amur in the 1870s.

While the comparably flat Western Siberia was at least fairly well

served by the gigantic Ob-Irtysh-Tobol-Chulym river system, the

mighty rivers of Eastern Siberia - the Yenisei, the upper course of

the Angara River (the Angara below Bratsk was not easily navigable

because of the rapids), and the Lena - were mostly navigable only in

the north-south direction.

An attempt to partially remedy the situation by building the

Ob-Yenisei Canal was not particularly successful. Only a railway

could be a real solution to the region's transportation

problems.

The first railroad projects in Siberia emerged after the completion

of the Moscow-Saint Petersburg Railway in 1851.

One of the first was the Irkutsk-Chita project, proposed by an

American entrepreneur W. Collins and supported by Transport Minister

Constantine Possiet with a view toward connecting Moscow to the Amur

river, and consequently, to the Pacific Ocean.

Siberia's governor, Nikolay Muravyov-Amursky, was anxious to advance

the colonisation of the Russian Far East, but his plans could not

materialize as long as the colonists had to import grain and other

food from China and Korea.

It was on Muravyov's initiative that surveys for a railroad in the

Khabarovsk region were conducted.

Before 1880, the central government had virtually ignored these

projects, because of the weakness of Siberian enterprises, a

clumsy bureaucracy, and fear of financial risk. Financial

minister Count Egor Kankrin wrote:

The idea of covering Russia with a railroad network not just

exceeds any possibility, but even building the railway from

Petersburg to Kazan must be found untimely by several

centuries.

By 1880, there were a large number of rejected and upcoming

applications for permission to construct railways to connect

Siberia with the Pacific but not eastern Russia.

This worried the government and made connecting Siberia with

central Russia a pressing concern.

The design process lasted 10 years.

Along with the route actually constructed, alternative

projects were proposed:

* Southern route: via Kazakhstan, Barnaul, Abakan and

Mongolia.

* Northern route: via Tyumen, Tobolsk, Tomsk, Yeniseysk

and the modern Baikal Amur Mainline or even through

Yakutsk.

Railwaymen fought against suggestions to save funds, for

example, by installing ferryboats instead of bridges over

the rivers until traffic increased.

The designers insisted and secured the decision to construct

an uninterrupted railway.

Unlike the rejected private projects that intended to connect

the existing cities demanding transport, the Trans-Siberian

did not have such a priority.

Thus, to save money and avoid clashes with land owners, it was

decided to lay the railway outside the existing cities.

Tomsk was the largest city, and the most unfortunate, because

the swampy banks of the Ob River near it were considered

inappropriate for a bridge.

The railway was laid 70 km to the south (instead crossing the

Ob at Novosibirsk), just a blind branch line connected with

Tomsk, depriving the city of the prospective transit rail

traffic and trade.

The railway was instantly filled to its capacity with local

traffic, mostly wheat.

Together with low speed and low possible weights of trains,

it upset the promised role as a transit route between Europe

and East Asia.

During the Russian-Japanese war, the military traffic to the

East almost disrupted the flow of civil freight.

Construction

Full-time construction on the Trans-Siberian Railway began in

1891 and was put into execution and overseen by Sergei Witte,

who was then Finance Minister.

Similar to the First Transcontinental Railroad in the USA,

Russian engineers started construction at both ends and

worked towards the centre.

From Vladivostok the railway was laid north along the right

bank of the Ussuri River to Khabarovsk at the Amur River,

becoming the Ussuri Railway.

In 1890, a bridge across the River Ural was built and the

new railway entered Asia.

The bridge across the Ob River was built in 1898 and the

small city of Novonikolaevsk, founded in 1883, metamorphosed

into a large Siberian centre-Novosibirsk.

In 1898, the first train reached Irkutsk and the shores of

Lake Baikal.

The railway ran on to the east, across the Shilka and the

Amur rivers and soon reached Khabarovsk.

The Vladivostok-Khabarovsk branch was built a bit earlier,

in 1897.

Russian soldiers, as well as convict labourers from Sakhalin

and other places were pressed into railway-building service.

One of the largest challenges was the construction of the Circum-Baikal

Railway around Lake Baikal, some 60 km (40 mi) east of Irkutsk.

Lake Baikal is more than 640 km (400 mi) long and over 1,600 m (5,000

feet) deep.

The line ended on each side of the lake and a special icebreaker ferryboat,

the SS Baikal, as well as a smaller one, the SS Angara, were built at

Newcastle upon Tyne, England, to connect the railway.

In the winter sleighs were used to move passengers and cargo from one

side of the lake to the other until the completion of the Lake Baikal

spur along the southern edge of the lake.

With the completion of the Amur River line north of the Chinese border

in 1916, there was a continuous railway from Petrograd to Vladivostok

that remains to this day the world's longest railway line.

Electrification of the line, begun in 1929 and completed in 2002,

allowed a doubling of train weights to 6,000 tonnes.

Effects

The Trans-Siberian Railway gave a great boost to Siberian agriculture,

facilitating substantial exports to central Russia and Europe.

It influenced the territories it connected directly, as well as those

connected to it by river transport.

For instance, Altai Krai exported wheat to the railway via the Ob

River.

As Siberian agriculture began to export cheap grain towards the West,

agriculture in Central Russia was still under economic pressure after

the end of serfdom, which was formally abolished in 1861.

Thus, to defend the central territory and to prevent possible social

destabilisation, in 1896 the government introduced the Chelyabinsk

tariff break (Челябинский тарифный перелом),

a tariff barrier for grain passing through Chelyabinsk, and a similar barrier in

Manchuria.

This measure changed the nature of export: mills emerged to create

bread from grain in Altai Krai, Novosibirsk and Tomsk, and many

farms switched to butter production.

From 1896 until 1913 Siberia exported on average 501,932 tonnes

(30,643,000 pood) of bread (grain, flour) annually.

The Trans-Siberian line remains the most important transportation

link within Russia; around 30% of Russian exports travel on the

line.

While it attracts many foreign tourists, it gets most of its use

from domestic passengers.

The Trans-Siberian is a vital link to the Russian Far East.

Today the Trans-Siberian Railway carries about 200,000 containers

per year to Europe.

Russian Railways intends to increase the volume of container traffic

on the Trans-Siberian still further by 2-2.5 time and is developing

a fleet of specialised cars and increasing terminal capacity at the

ports by a factor of 3 to 4!

By 2010, the volume of traffic between Russia and China could reach

some 60 million tons, most of which will go by the

Trans-Siberian.

With perfect coordination of the participating countries' railway

authorities, a trainload of containers can be taken from Beijing

to Hamburg, via the Transmongolian and Transsiberian lines in as

little as 15 days, but typical cargo travel times are usually

significantly longer - e.g., typical cargo travel time from Japan

to major destinations in European Russia was reported as around

25 days.

Passenger fares

Return tickets from Central Europe to Vladivostok and back can be

as cheap as €250.00 with so called CityStar or Sparpreis Europa

special offers.

In addition a reservation supplement for long-distance trains is

mandatory, the prices range between €30.00 to €60.00

each way for trains in four-berth sleeper on the Trans-Siberian

railroad.

Overall, buying tickets for Russian trains in Germany, the Czech

Republic or Poland can be cheaper and easier (language-wise) than

in Russia.

In addition to these services, a number of privately-chartered

services are operated and one tour operator even commissioned

the construction of their own train, jointly owned by themselves

and Russian railways.

The train, officially named Golden Eagle Trans-Siberian Express

was launched on 26 April 2007 by Prince Michael of Kent.

Routes

In general, the lower the train number the fewer stops it makes

and therefore the faster the journey.

The train number makes no difference to the duration of border

crossings.

Map of the Trans-Siberian Railway,

showing some of the alternative routes.

Trans-Siberian line

A commonly used main line route is as follows.

Distances and travel times are from the schedule of train

No.002M, Moscow-Vladivostok.

* Moscow, Yaroslavsky Rail Terminal (0 km, Moscow Time).

* Vladimir (210 km, MT)

* Nizhny Novgorod (461 km, 6 hours, MT) on the Volga River.

Its railroad station is still called by its old Soviet name Gorky,

and is so listed in most timetables.

* Kirov (917 km, 13 hours, MT) on the Vyatka River.

* Perm (1,397 km, 20 hours, MT+2) on the Kama River

* Official boundary between Europe and Asia (1,777 km),

marked by a white obelisk.

* Yekaterinburg (1,778 km, 1 day 2 h, MT+2) in the Urals,

still called by its old Soviet name Sverdlovsk in most timetables.

* Tyumen (2,104 km)

* Omsk (2,676 km, 1 day 14 h, MT+3) on the Irtysh River

* Novosibirsk (3,303 km, 1 day 22 h, MT+3) on the Ob River

* Krasnoyarsk (4,065 km, 2 days 11 h, MT+4) on the Yenisei River

* Taishet (4,483 km), junction with the Baikal-Amur Mainline

* Irkutsk (5,153 km, 3 days 4 h, MT+5) near Lake Baikal's

southern extremity

* Ulan Ude (5,609 km, 3 days 12 h, MT+5)

* Junction with the Trans-Mongolian line (5,622 km)

* Chita (6,166 km, 3 days 22 h, MT+6)

* Junction with the Trans-Manchurian line at Tarskaya (6,274 km)

* Birobidzhan (8,312 km, 5 days 13h), the capital of Jewish

Autonomous Region

* Khabarovsk (8,493 km, 5 days 15 h, MT+7) on the Amur River

* Ussuriysk (9,147 km), junction with the Trans-Manchurian line

and Korea branch

* Vladivostok (9,289 km, 6 days 4 h, MT+7), on the Pacific Ocean

Services to North Korea continue from Ussuriysk via:

* Primorsk (9,257 km, 6 days 14h, MT+7)

* Khasan (9,407 km, 6 days 19h, MT+7, border with North Korea)

* Tumangang (9,412 km, 7 days 10h, MT+6, North Korean side of the border)

* Pyongyang (10,267 km, 9 days 2h, MT+6)

There are many alternative routings between Moscow and Siberia. For example:

* Some trains would leave Moscow from Kazansky Rail Terminal

instead of Yaroslavsky Rail Terminal; this would save some 20 km off

the distances, because it provides a shorter exit from Moscow onto

the Nizhny Novgorod main line.

* One can take a night train from Moscow's Kursky Rail Terminal

to Nizhny Novgorod, make a stopover in the Nizhny and then transfer

to a Siberia-bound train

* From 1956 to 2001 many trains went between Moscow and Kirov

via Yaroslavl instead of Nizhny Novgorod. This would add some 29

km to the distances from Moscow, making Vladivostok Kilometer 9,288.

* Other trains get from Moscow (Kazansky Terminal) to

Yekaterinburg via Kazan.

* Between Yekaterinburg and Omsk it is possible to travel via

Kurgan Petropavl (in Kazakhstan) instead of Tyumen.

* One can bypass Yekaterinburg altogether by travelling via

Samara, Ufa, Chelyabinsk, and Petropavl; this was historically the

earliest configuration.

Depending on the route taken, the distances from Moscow to the

same station in Siberia may differ by several tens of

kilometers.

Trans-Manchurian line

The Trans-Manchurian line, as e.g. used by train No.020, Moscow-Beijing

follows the same route as the Trans-Siberian between Moscow and Chita,

and then follows this route to China:

* Branch off from the Trans-Siberian-line at Tarskaya (6,274 km from Moscow)

* Zabaikalsk (6,626 km), Russian border town

* Manzhouli (6,638 km from Moscow, 2,323 km from Beijing), Chinese border town

* Harbin (7,573 km, 1,388 km)

* Changchun (7,820 km from Moscow)

* Beijing (8,961 km from Moscow)

The express train (No.020) travel time from Moscow to Beijing is

just over six days.

There is no direct passenger service along the entire original

Trans-Manchurian route (i.e., from Moscow-or anywhere in Russia-

west-of-Manchuria-to Vladivostok via Harbin), due to the obvious

administrative and technical (gauge break) inconveniences of

crossing the border twice.

However, assuming sufficient patience and possession of appropriate

visas, it is still possible to travel all the way along the original

route, with a few stopovers (e.g. in Harbin, Grodekovo, and

Ussuriysk).

Such an itinerary would pass through the following points

from Harbin east:

* Harbin (7,573 km from Moscow)

* Mudanjiang (7,928 km)

* Suifenhe (8,121 km), the Chinese border station

* Grodekovo (8,147 km), Russia

* Ussuriysk (8,244 km)

* Vladivostok (8,356 km)

Trans-Mongolian line

The Trans-Mongolian line follows the same route as the Trans-Siberian

between Moscow and Ulan Ude, and then follows this route to Mongolia

and China:

* Branch off from the Trans-Siberian line (5,655 km from Moscow)

* Naushki (5,895 km, MT+5), Russian border town

* Russian-Mongolian border (5,900 km, MT+5)

* Sükhbaatar (5,921 km, MT+5), Mongolian border town

* Ulan Bator (6,304 km, MT+5), the Mongolian capital

* Zamyn-Üüd (7,013 km, MT+5), Mongolian border town

* Erenhot (842 km from Beijing, MT+5), Chinese border town

* Datong (371 km, MT+5)

* Beijing (MT+5)

Cultural importance

* The Trans-Siberian Railway is the theme for the Trans-Siberian

Railway Panorama and 1900 Trans-Siberian Railway Fabergé egg.

* The Corto Maltese comic Corto Maltese en Sibérie has the Trans-

Siberian Railway as part of the story that takes place in the Russian

Revolutionary period of the 20th century.

* The cult film Horror Express starring Peter Cushing, Christopher

Lee and Telly Savalas is set aboard the railway.

* In the play Fiddler on the Roof and the film version, Tevye's

daughter, Hodel, takes the Trans-Siberian Railway to Siberia after

her fiancé is exiled there.

* The 2008 thriller Transsiberian takes place on the railway.

For more information about

Trans-Siberian Railway see Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This page was retrieved and condensed from

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trans-Siberian_Railway)

see Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, December 2008.

All text is available under the terms of the

GNU Free Documentation License

(see

Copyrights for details).

About Wikipedia

Disclaimers

This information was correct in December 2008. E. & O.E.

Site Index

Back to Top

Photos Index

Thanks for coming, I hope you

have enjoyed it, will recommend

it to your friends,

and will come

back later to see my site developing

and expanding.

I'm trying to make my pages

enjoyable and trouble free for everyone,

please

let me know of any mistakes

or trouble with links, so I can

fix any problem

as soon as possible.

These pages are best viewed with monitor

resolution set at 640x480 and kept simple

on purpose so everyone can enjoy them

across all media and platforms.

Thank you.

Webmaster

Trans-Siberian Express map courtesy Wikipedia,

Trans-Siberian Express map courtesy Wikipedia,

Trans-Siberian Express map courtesy Wikipedia,

Trans-Siberian Express map courtesy Wikipedia,  View from the rear platform of the

View from the rear platform of the  Map of the Trans-Siberian Railway,

Map of the Trans-Siberian Railway,